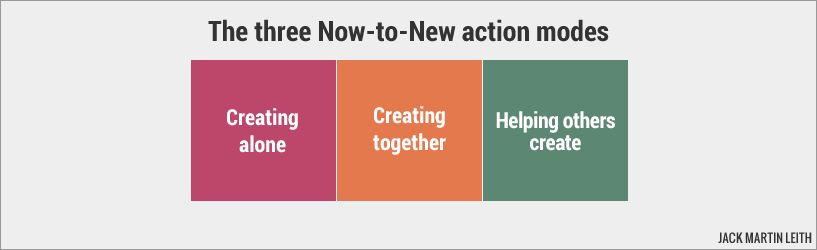

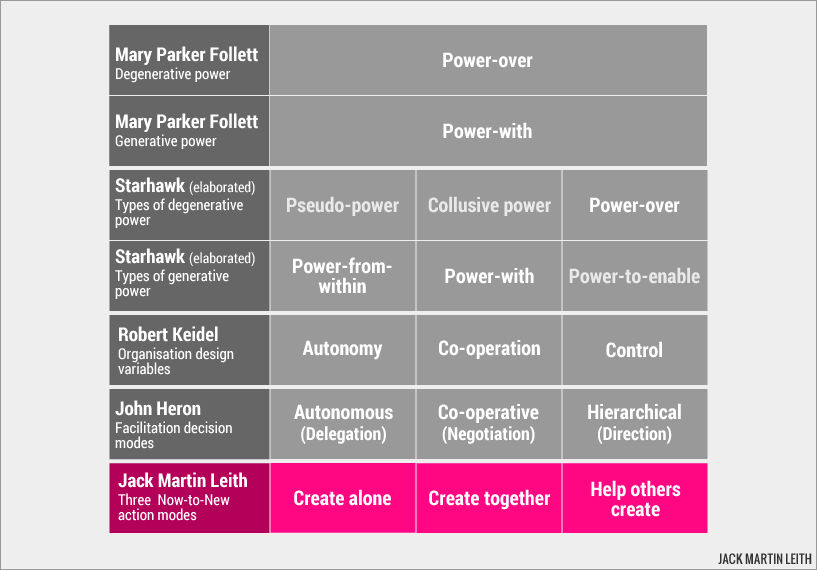

In this article, distilled from a much longer and more detailed original, I seek to make the case that successful Now-to-New projects require a judicious blend of three action modes:

![]() Creating alone.

Creating alone.

![]() Creating together.

Creating together.

![]() Helping others create, in a role such as facilitator, coach or thinking partner.

Helping others create, in a role such as facilitator, coach or thinking partner.

The consequences of deploying each action mode can be either generative (aimed at maximising the amount of value that will be generated downstream) or degenerative (aimed at diminishing or nullifying potential value, or generating anti-value). Degenerative consequences are often unconscious and unintended.

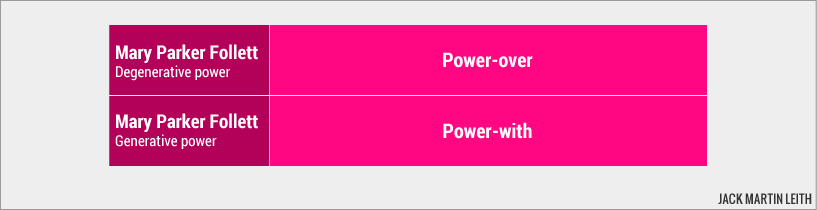

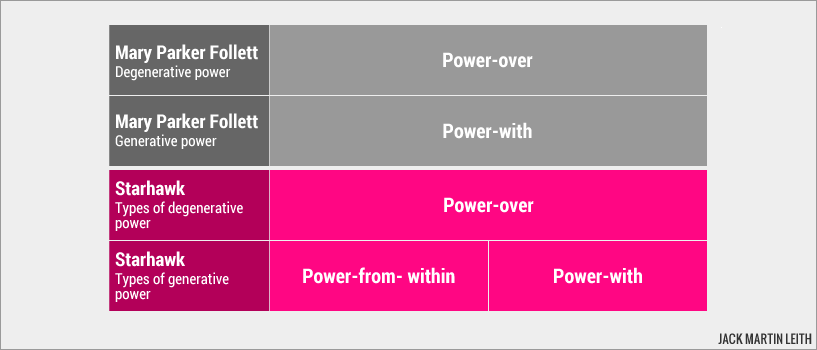

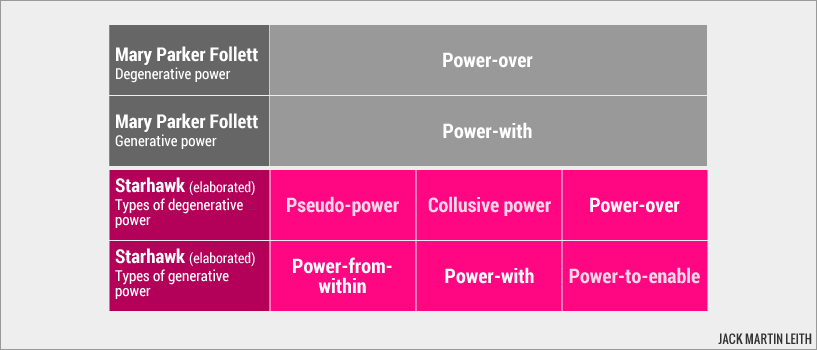

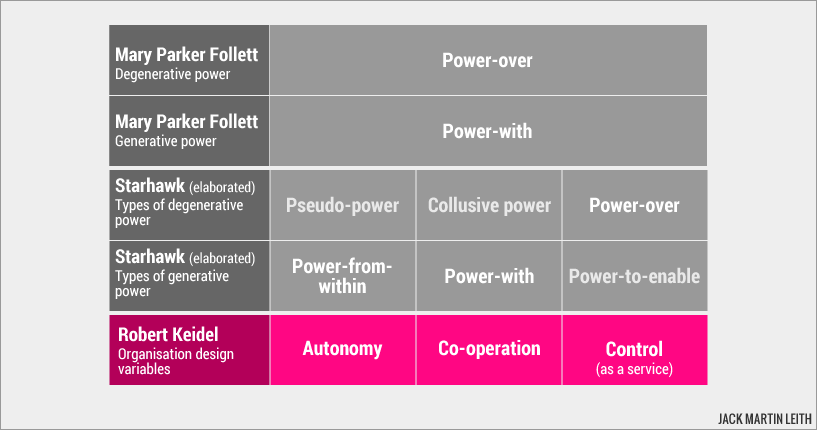

The original version of this article starts with a section about the nature of power. In this abridged version I’ll summarise by saying that power is synonymous with agency, and go straight to talking about the power distinctions commonly attributed to Mary Parker Follett and Starhawk,

Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933) was an American social worker, management consultant and philosopher, and a pioneer in the fields of organisational theory and organisational behaviour. She has been called “the mother of modern management.” (Source: Wikipedia.)

Mary Parker Follett originated the distinctions of power-over (coercive or oppressive power) and power-with (collaborative power). Cat Swetel claims (view source) that Follett identified a third kind of power, power-to, defined as “the power we have to create new things”. However, I can find no mention of this beyond Swetel’s article.

“Power is one of the key ideas in management, and so is the concept of authority. However, most studies on power are rather instrumental, dealing with the place of power in management, and how to achieve it. Less attention has been paid to the essential concepts of power and authority themselves in management thought and how they have evolved. To clarify these concepts, and to better understand the notions of power and authority in management and their proper use in organisations, this paper goes back to one of the pioneers in management thought: Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933). She had an original vision of power, holding that genuine power is not ‘power-over’, but ‘power-with.’”

Source: Power, Freedom and Authority in Management: Mary Parker Follett’s ‘Power-With’ by Domènec Melé & Josep M. Rosanas, Philosophy of Management, volume 3, pages 35–46 (2003) | My emphasis

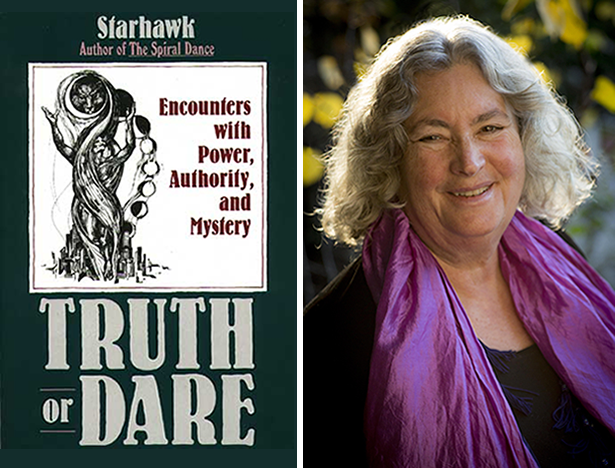

Starhawk’s three types of power (1991)

Click on image or here to order a copy of the book from Amazon UK

Starhawk (born Miriam Simos) is an American writer, teacher and activist, best known as a theorist of feminist neopaganism and ecofeminism.Her first book The Spiral Dance, published in 1979, was popular with many of those involved in the Goddess movement.

In 2013, she was listed in Watkins’ Mind Body Spirit magazine as one of the 100 Most Spiritually Influential Living People (Wikipedia)..

In her third book, Truth or Dare: Encounters with Power, Authority, and Mystery (1988), she reprises — without credit — Mary Parker Follett’s concepts of power-over and power-with, adding a third that she named power-from-within.

Power-from-within is linked to the mysteries that awaken our deepest abilities and potential.

Power-with is social power, the influence we wield among equals.

Power-over is linked to domination and control.Source: The Three Types of Power: an excerpt from Truth or Dare by Starhawk.

Rectifying the flaw in Starhawk’s power model

Starhawk contrasts power-over with power-with and power-from-within in a way that reflects 1970s feminist ideology. Power-over is bad power. It is exercised predominantly by men, the misogynistic patriarchy, in order to oppress women. Power-with is good power, likewise power-from-within. These good forms of power are exercised mainly by women.

But Starhawk, whose books I have read and enjoyed, has made some fundamental errors, either deliberately or unintentionally.

- The degenerative form of power-with is not power-over. It is collusive power, where two or more people act together for self-serving or nefarious purposes.

- The degenerative form of power-from-within is not power-over. It is pseudo-power, often showing up as self-importance or bravado.

- The generative form of power-over is not power-with or power‑from‑within, but power‑to‑enable.

Power-over vs. power-to-enable

My working definition of power is “the capability of accomplishing something, with or without the use of coercion, for the benefit of oneself, others or both.”

Power-over can therefore be defined as “the capability of accomplishing something with the use of coercion for the benefit of oneself.”

And so its converse must be “the capability of accomplishing something without the use of coercion for the benefit of others.”

On this basis, we could refer to the generative form of power-over as altruistic (“showing unselfish concern for the welfare of others”) power. Instead, I’ve chosen to call it power-to-enable, for reasons that will become apparent when I introduce the work of Robert Keidel and John Heron in a few moments.

Power-over isn’t always about deliberately imposing one’s will on others and constraining their power-from-within. Sometimes it’s just a distorted form of power-to-enable, such as that displayed by an inept facilitator who sets the group a tightly-specified task, unwittingly closing-off creative possibilities and hindering the group’s progress towards its goals. No malice is intended.

Pseudo-power

Pseudo-power was prominent in the girl power movement that flourished during the 1990s. Sloganeering, bravado and ‘attitude’ were adopted as proxies for real autonomous power. A more recent example of the phenomenon is described by Jill P. Weber in Girl Power or Pseudo-Power? on the Psychology Today website.

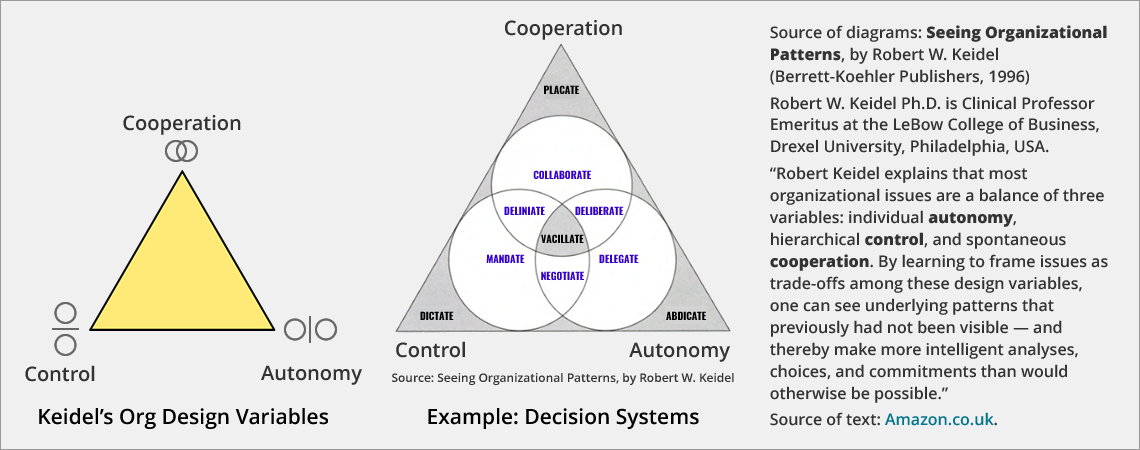

Robert Keidel’s three organisational design variables (1995)

“People want power because they want autonomy.”

Source: Julie Beck, on The Atlantic (reporting on a study conducted by researchers from University of Cologne, University of Groningen, and Columbia University) | Read the article: People want power because they want autonomy by Julie Beck

Robert Keidel is Clinical Professor Emeritus at the LeBow College of Business, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA.

In his insightful book, Seeing Organizational Patterns: A New Theory and Language of Organizational Design, he introduces an elegant model for improving the design of organisational systems in such areas as decision making, employee rewards and meeting management.

The central idea in the book is that an effective design must employ a judicious combination of three variables: autonomy, cooperation and control. Note that these labels are neutral and do not fall into the trap of thinking that autonomy and co‑operation are ‘good’, whereas control is ‘bad’.

The following graphic shows Keidel’s model applied to the design of decision systems, with the viable options indicated in blue type.

View an enlarged version of the Decision Systems example

When people encounter the word control, they tend to think about its degenerative form, which corresponds with power-over as defined by Starhawk and Mary Parker Follett. The autonomy of an individual, group or institution is being constrained or otherwise manipulated to the benefit of the individual, group or institution exercising control.

There is a benign, generative form of control I call control as a service. Examples include Houston Mission Control Center, air traffic control and railway signalling systems.In the military world, people began studying leadership a couple of thousand years ago — and interestingly, the military are less dismissive of management. Even more interestingly, they talk about something else we do not talk about in business at all. They have a third concept: command.

In military language, ‘command and control’ covers the various ways in which direction is given and the effects of actions are monitored. But in the language of business, ‘command and control’ has become shorthand for ‘authoritarian micro-management’, which is just one — usually dysfunctional — way, of exercising it. Giving the words ‘command and control’ this negative sense is a strange choice, because business is quite keen on ‘control’. Equating ‘command and control’ with ‘authoritarian micro-management’ is a category error — it confuses ‘fruit’ with ‘rotten apples’. Not using the word will not make the activity referred to as ‘command’ go away. NATO defines command as: ‘The authority invested in an individual for the direction, co-ordination and control of military forces’. Co-ordination and control are classic roles of management. So perhaps the bit we don’t feel so comfortable with is ‘direction’.

Command is something granted to someone by an external party. The external party confers rights of authority and along with them go responsibilities, duties and accountability. Responsibilities may be delegated or shared, but the commander remains accountable for the results. In the British Armed Forces, command is ultimately granted by the Sovereign: in the United States, by the President. In businesses it is granted by the owners of the business, who are most commonly the shareholders.

Command is as unavoidable in the business world as it is in the military one. Because it is a real requirement, somebody has got to do it, and because of its central importance in business we have to talk about it. So we do: we include it under ‘leadership’. As a result, we cause confusion.

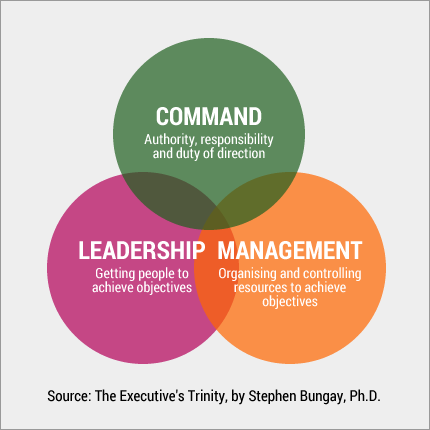

Business thinking suffers from offering the simple duality of management and leadership, and the leadership literature contains futile debates because of a failure to distinguish leadership from command. There is a trinity of command, leadership and management, and both officers and executives have to practise all three, as illustrated [below].

The executive’s trinity: management, leadership – and command (pdf; 34pp) by Stephen Bungay, Ph.D., a director of Ashridge Strategic Management Centre

In the next image, you can see the relationship between Robert Keidel’s design variables and the power distinctions made by Starhawk and Mary Parker Follett. The thinking behind my elaboration of Starhawk’s power model should now be apparent.“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. This is the captain welcoming you aboard our flight to Chicago. We’re just completing the paperwork and we’ll be pushing back in a few minutes. I have to inform you that air traffic control has been abolished and that, as of today, planes will self-organise. My first officer and I will do our best to get you there safely and on time. Now fasten your seat belt, sit back, relax and enjoy the flight.”

Robert Keidel’s design variables suggest that if we want to conceive a new creation, bring it into existence and realise its value generation potential, then solo work and collaborative work are not alternatives — both are essential, and must be properly integrated. Further, some form of enabling function, such as a coach, facilitator, project leader, team leader or full-blown mission control function, needs to be in place.

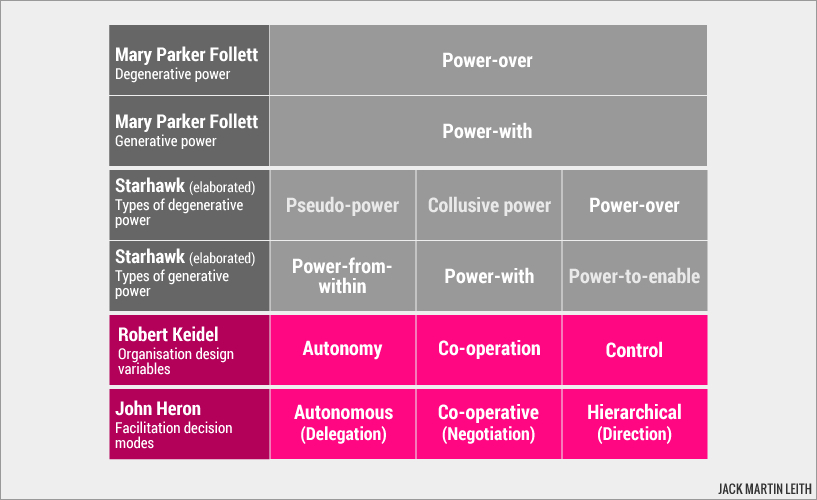

John Heron’s system of facilitation decision modes adds weight to this proposition.

Read more about control as a service

John Heron’s three facilitation decision modes (1999)

John Heron (1928–2022) was a psychologist, the originator of a participatory research method called co‑operative inquiry, and an eminent group facilitator and educator in the field of co‑counselling. In his final years, he was co-director of the South Pacific Centre for Human Inquiry, based in Auckland, New Zealand. He founded and ran the groundbreaking Human Potential Research Project (later, the Human Potential Research Group) at University of Surrey from 1970 to 1977, and was one of the founders in the UK of each of the following: Association of Humanistic Psychology Practitioners, Co‑counselling International, Institute for the Development of Human Potential, New Paradigm Research Group, and Research Council for Complementary Medicine. Source: Wikipedia.

In The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook (pdf), John Heron describes the three decision modes available to facilitators: hierarchical (he also refers to this as direction), where the facilitator makes the decision for group members; co-operative (a.k.a. negotiation), where the facilitator reaches the decision with group members; and autonomous (a.k.a. delegation), where the facilitator hands over the decision-making process to group members. The labels are neutral, as is the case with Robert Keidel’s model.

The facilitator weaves the three modes into the design of a particular co-creation meeting and deploys all of them when facilitating the meeting, moving effortlessly between modes in response to unfolding circumstances, regardless of whether he or she is working one-to-one, with a small group, or with a large one.

Visit the John Heron Human Inquiry Archive, where you can download some of his works in their entirety“The hierarchical mode Here you, the facilitator, direct the learning process, exercise your power over it, and do things for the group. You lead from the front by thinking and acting on behalf of the group. You decide on the objectives and the programme, interpret and give meaning, challenge resistances, manage group feeling and emotion, provide structures for learning and honour the claims of authentic behaviour in the group. You take full responsibility, in charge of all major decisions on all dimensions of the learning process.

The co-operative mode Here you share your power over the learning process and manage the different dimensions with the group. You enable and guide the group to become more self-directing in the various forms of learning by conferring with them and prompting them. You work with group members to decide on the programme, to give meaning to experiences, to confront resistances, and so on. In this process, you share your own view which, though influential, is not final but one among many. Outcomes are always negotiated. You collaborate with the members of the group in devising the learning process: your facilitation is co-operative.

The autonomous mode Here you respect the total autonomy of the group: you do not do things for them, or with them, but give them freedom to find their own way, exercising their own judgment without any intervention on your part. Without any reminders, guidance or assistance, they evolve their programme, give meaning to what is going on, find ways of confronting their avoidances, and so on. The bedrock of learning is unprompted, self-directed practice, and here you delegate it to the learner and give space for it. This does not mean the abdication of responsibility. It is the subtle art of creating conditions within which people can exercise full self-determination in their learning.”

Source: John Heron, The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook (pdf; 428pp). He is talking about the facilitation of learning groups, but the three modes apply equally to action-focused groups.

Keidel – Heron correlation

The next graphic shows the strong correlation between John Heron’s facilitation decision modes and Robert Keidel’s organisation design variables.

Was John Heron influenced by Robert Keidel’s model? Seeing Organizational Patterns was published four years before The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook, so it’s possible, although Heron and Keidel inhabited very different worlds. My hope is that both men uncovered a universal truth independently of each other.

John Heron created the decision mode model for the benefit of facilitators, particularly those involved in developmental groupwork. But the model should be applied by all those engaged in catalysing and supporting Now-to-New work, such as coaches, project leaders, team leaders and bosses.

The three Now-to-New action modes

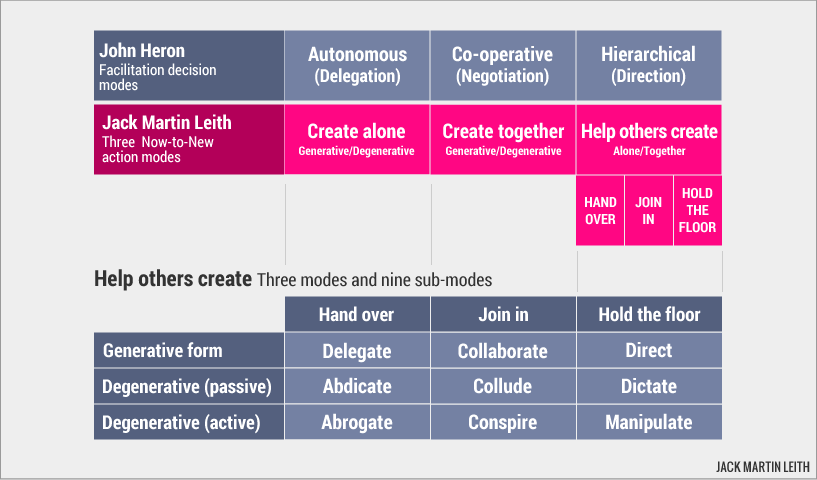

Each action mode (creating alone, creating together, helping others create) can have generative or degenerative consequences, which can be unintentional or deliberate.

The original version of this article explores the nine sub-modes in detail. They appear in the image below.

If there is sufficient interest I will publish the original version as a webpage, pdf document or both.

Helping others create means helping someone create alone, as well as helping two or more people create together.

It consists of three modes of enablement that correspond with John Heron’s facilitation decision modes: Delegate (corresponds with his autonomous mode), Collaborate (co-operative) and Direct (hierarchical).

What this means for Now-to-New practitioners

When creating alone

![]() Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

In 1545, Jacopo da Pontormo scored a major commission from Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici to paint the main chapel of Florence’s church of San Lorenzo. A contemporary of masters like Michelangelo, Pontormo was a distinguished but aging artist who was eager to secure his legacy.

Pontormo knew he needed to make these frescoes the crowning achievement of his career, so he sealed off the entire chapel. He built walls, erected partitions, and hung blinds so that nobody could steal his ideas or sneak an early peek. Trusting no one, he chased away local youth and kept human contact to a minimum. He spent eleven years holed up, painting Christ on Judgement Day, Noah’s ark, and Creation itself.

Pontormo died before his work on the chapel was done, and none of it survives, but the legendary Renaissance writer Vasari visited the site soon after the painter’s death. He reported a confused composition and unsettling lack of alignment, scenes that ran into each other every which way. Robert Greene writes, “These frescoes were visual equivalents of the effects of isolation on the human mind: a loss of proportion, an obsession with detail combined with an inability to see the larger picture.”

Source: Why Seclusion Is the Enemy of Creativity, by Eliot Peper, on Harvard Business Review

![]() Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

When creating together

![]() Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

![]() Know how to combine the three kinds of Now-to-New action modes.

Know how to combine the three kinds of Now-to-New action modes.

![]() Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

When helping others create

![]() Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

![]() Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

![]() Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the enablement modes.

Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the enablement modes.

Continue reading

How the term Now-to-New came into being

Now-to-New and the seven kinds of work

Readiness work sets the Now-to-New project in motion

A selection of proprietary and open source Now-to-New methods

Search the site

Not case sensitive. Do not to hit return.